Prince in Hell

Prince in Hell (

Prinz in Hölleland) - dir. Michael Stock - 1993 - Germany

The term teen angst likely found itself a visual, cinematic reference in the 1980s, but the 1990s morphed into a real state of being, an unmistakable characteristic of the disgruntled youth, not only of the United States, but of the entire world. This angst extended beyond the teenage years, with films like Noah Baumbach’s

Kicking and Screaming or any of Gregg Araki’s films, creating separate facets of this global existentialism. From the post-undergraduate dormancy of the

Kicking and Screaming boys and girls to the what-are-we-doing-in-this-godless-world-of-scientologists-and-violence teenagers that filled Araki’s screen, these anxieties spanned the gamut of youth, unaware of their place, purpose, and future. These sentiments still exist in cinema from all over the world, like Jia Zhang-Ke’s

Unknown Pleasures (China) or Bruno Dumont’s

The Life of Jesus [

La Vie de Jésus] (France) to name a few, adding to the ever-increasing canon of what-are-we-doing-here malaise in cinema.

Prince in Hell closely fits into the faded genre of New Queer Cinema, made famous by people like Todd Haynes, Bruce La Bruce, and Araki. While the gays were certainly not the only ones who held these anxieties, how fitting these feelings would be for a group of people long ignored, continuously hated with their history and their patriarchs being ravished by the crisis of AIDS, an epidemic upon which the government tried to turn a blind eye.

Prince in Hell stands as a forgotten piece of New Queer Cinema, a film ripe with dissatisfaction, fear, and the shattered dreams of a generation.

There was a film that I so violently disliked, I could hardly bring myself to write about it, called

FAQs.

FAQs, made in 2005 by Everett Lewis, tried to stretch the genre of New Queer Cinema past the 90s, only with a knowing-eye, with a well-noted study of queer theory. In the film, all of the themes and aesthetic motifs, like music and fashion, seemed painfully contrived, leaving not a single moment for the audience to intellectually deduct a damn thing.

Prince in Hell has all of these themes established for itself, most importantly the desire for a new family structure. Only, here, characters don’t throw out lines like, “We need to create a new family structure to combat against the patriarchal, republican assholes of our country.” Perhaps that wasn’t the line verbatim, but you get the point.

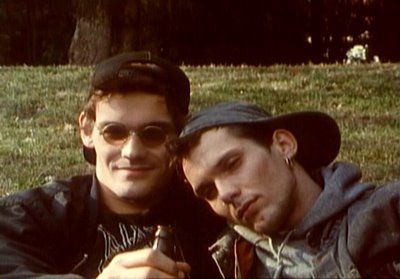

Prince in Hell, like so many other NQC films, was of its time, and therefore created the style, themes, and motifs of a genre a director like Lewis so shamelessly wanted to revive. A commune of social rejects form in

Prince in Hell, consisting of court-jester Firelfranz (Wolfram Haack), junky Jockel (director Stock), alcoholic, lovelorn Stefan (Stefan Laarmann), constantly-horny Micha (Andreas Stadler), his wide-eyed eight-year-old son Sascha (Nils Leevke-Schmidt), and his fed-up, baby’s-momma Sabine (Simone Spengler). They all live in a mobile home, with various others joining them for parties and eating, each looking out for the other and seeking to combat the treacherous world around them. Micha is a terrible father; his varying sexual interests keep his mind away from his child, so the Derek Jarman-y Firelfranz assumes the role of care-giver to the boy. Jockel and Stefan are in a stormy relationship. Stefan cares about politics and monogamy, while Jockel’s possible interests in either have hit the downward slope, possibly due to his heroin addiction.

The lives of the three central characters, the love triangle of Jockel, Stefan, and Micha, is paralleled by a puppet-show, conducted by Firelfranz about a young prince banished to the forest of Hell. In the forest, a petrified Garden of Eden, he lives with his lover but suffers from the constant torment and temptation of the evil Magician. The Magician offers him powders and potions that distract him from his one true love, as he struggles to once again get the approval of his father, the King. If you don’t spot the metaphor, you should probably open your eyes. Thankfully, the film doesn’t treat these parallels as a way to drive the point deeper, but as both a clever narrative tool and a way for the young Sacha to interpret the frightening world around him. This world of ambiguous love and sex, mind-altering substances, and rejection exists without real acknowledgement from the naïve young Sascha, and Firelfranz’s fable allows for the interaction and interest in the concerns of the world for the boy. He is the not-so-blissfully ignorant viewer, unconsciously blind to the hardships around him and a reminder of the scope of these anxieties, these ailments of a generation (and subsequent generations).

On another level,

Prince in Hell addresses the cultural terrors of a newly-united Germany. As a film like Wim Wenders’

Wings of Desire (

Der Himmel über Berlin) exposes the worldview of Germany just before the fall of the Berlin Wall,

Prince in Hell carefully exposes the frightening reality of post-Wall Germany, where, it appears, not much has changed. Through radiocasts, Stock clues our audience into the world outside of this commune, where xenophobia and violence run wild. One might get the false impression that the commune exists as a peaceful outlet from the societal anguish, but the characters soon recognize the holding power of the outside world upon their “family.” Treks outside of the commune elicit frowning looks from on-lookers, animalistic sexual encounters, skinhead violence, and damaging drug intakes. All of these elements sadly bring themselves back to the family, where hopes of romanticized escapism are tarnished. Jockel’s drug addiction and failing interest in the good causes which the commune supported rub off on the rest of the characters. He introduces Micha, an easily tempted young man, to heroin and ignores the romantic leanings toward Stefan, who quickly becomes irrevocably frustrated with the entire situation, while not being able to break himself away from it. Micha’s free-love, experimental ways distance him further from his son and sparks hatred from Sabine, the boy’s mother. Even within this refuge, the hatred of the outside world, of a falsely-liberated Germany, seeps within.

After watching Araki’s

The Doom Generation (which I will be writing about, again, soon) with a friend of mine, he commented about the bleak conclusion of what began as a raunchy, spunky black comedy. While

Prince in Hell is hardly the riotous comedy

The Doom Generation is, I can anticipate a strong, perhaps disgusted reaction at the finale of our film. Whereas something like

FAQs strategically tied a pink bow around a tale of misguided gay activism,

Prince in Hell doesn’t, leaving us a terrifying sense of gloom.

Prince in Hell’s worldview tells us that, essentially, there is no escape, and despite the admirable efforts of small groups of people, the struggle is endless. The torch is metaphorically handed to the young Sascha, but a lingering question remains. Has a world as fucked up as ours jaded the youth? And has this jadedness given us no hope for our future? Time, of course, will tell, and while

Prince in Hell may not have meant much to viewers upon its release (its IMDb rating is shockingly low), you can always throw your appreciation out to a cultural memoir, especially one whose dealings refuse to go away.

Finally seeing John Cameron Mitchell's Shortbus, as it doesn't come here until Thanksgiving.

Finally seeing John Cameron Mitchell's Shortbus, as it doesn't come here until Thanksgiving. Going to Grey Gardens: The Musical.

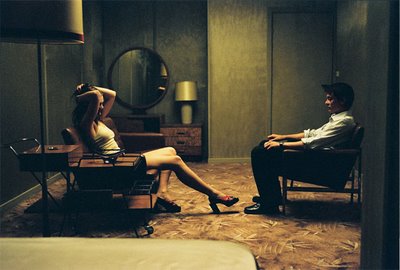

Going to Grey Gardens: The Musical. And POSSIBLY, dressing up as Rosanna Arquette from Crash for Halloween. I'm not much for dressing in drag, even for Halloween, even though I went as Yoko Ono performing "Cut Piece" last year. So, if it does happen, expect lewd photos sometime in November. Adieu!

And POSSIBLY, dressing up as Rosanna Arquette from Crash for Halloween. I'm not much for dressing in drag, even for Halloween, even though I went as Yoko Ono performing "Cut Piece" last year. So, if it does happen, expect lewd photos sometime in November. Adieu!