Sebastiane - dir. Derek Jarman, Paul Humfress - 1976 - UK

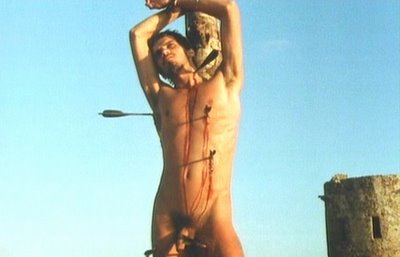

Sebastiane - dir. Derek Jarman, Paul Humfress - 1976 - UKFile this in between Claire Denis' Beau travail and Nagisa Oshima's Gohatto (Taboo) in the category of homoerotic mood poems set on female-less military grounds where authority and desire are synonymous. Derek Jarman's first feature, Sebastiane, reinterprets the story of St. Sebastiane, one of the first recognizable Christian martyrs of the Roman Empire with a visual cue from one of Mantegna's famous Renaissance paintings of the saint. Visuals are really all that matter here. Despite this, I would guess saying that I highly doubt Sebastiane appeals to any sect of Christians would be a grave understatement.

Instead of a historical reenactment of the events, Jarman offers us a fantasy, beginning in a Ken Russell-style decadence and ending in the remote Italian wasteland (the Russell comparison is not an overstatement, as Jarman began his career as an art director for Russell on The Devils and Savage Messiah). Though spoken in vulgar Latin, historical inaccuracies don't matter (St. Sebastian actually met his maker by stones, not arrows). Aided with a score by Brian Eno, Sebastiane focuses instead on mood, a dream piece of power, desire, and strangely-interpreted faith. Though a favorite in the palace, Sebastiane (Leonardo Trevilglio) was sent into exile after disagreeing with the king with his Christian beliefs. It's in exile, where his beauty attracts the interests of the Roman soldier Severus (Barney James), heading the troup, and where Sebastiane eventually meets his death. It is here, in exile, where the film shifts from a Ken Russell film to a Pasolini one, in which religious figures become feitishized sexual figures. More than simply a sexual figure, Sebastiane represents the deviation of order, and it's in this deviation that he is both desirable and rejecting.

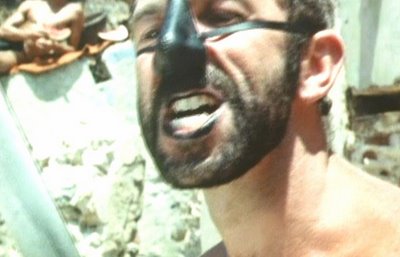

Instead of a historical reenactment of the events, Jarman offers us a fantasy, beginning in a Ken Russell-style decadence and ending in the remote Italian wasteland (the Russell comparison is not an overstatement, as Jarman began his career as an art director for Russell on The Devils and Savage Messiah). Though spoken in vulgar Latin, historical inaccuracies don't matter (St. Sebastian actually met his maker by stones, not arrows). Aided with a score by Brian Eno, Sebastiane focuses instead on mood, a dream piece of power, desire, and strangely-interpreted faith. Though a favorite in the palace, Sebastiane (Leonardo Trevilglio) was sent into exile after disagreeing with the king with his Christian beliefs. It's in exile, where his beauty attracts the interests of the Roman soldier Severus (Barney James), heading the troup, and where Sebastiane eventually meets his death. It is here, in exile, where the film shifts from a Ken Russell film to a Pasolini one, in which religious figures become feitishized sexual figures. More than simply a sexual figure, Sebastiane represents the deviation of order, and it's in this deviation that he is both desirable and rejecting. Though co-directed by Paul Humfress, Sebastiane establishes some of Jarman's signature motifs. Sebastiane is Brian Eno's first music for film (he would later go on to score both Jubilee and Blue). The film would also mark our first encounter with Jarman's sexual fetish. Like the existence of contrary light and dark women in Lynch or 50s period dress and high heels for Wong Kar-wai, Jarman's sexual fetish would be the slow-motion love-making of immaculately-sculpted, anonymous men. The fetish would present itself fully in The Angelic Conversation and best during a scene in The Last of England, where two terrorist-masked men would fuck on top of a British flag. More importantly, we first encounter the character of opposition in Jarman's films. After a discussion with Bradford, we came to realize that this character exists in most every of Jarman's films, the cunning provocateur, sort of like a Neanderthal Iago from Othello. This character is featured in both The Garden and Edward II as the instigator of humiliation or destruction of the central figure. He exists as Maximus (Neil Kennedy) in Sebastiane, a man of vulgar speech and carnal nature. In one particular scene (pictured above), he takes black chalk and rubs it across his lips and eyebrows like a sinister application of make-up designed not to be a beauty product, but the very opposite.

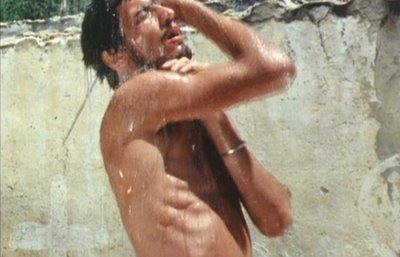

Though co-directed by Paul Humfress, Sebastiane establishes some of Jarman's signature motifs. Sebastiane is Brian Eno's first music for film (he would later go on to score both Jubilee and Blue). The film would also mark our first encounter with Jarman's sexual fetish. Like the existence of contrary light and dark women in Lynch or 50s period dress and high heels for Wong Kar-wai, Jarman's sexual fetish would be the slow-motion love-making of immaculately-sculpted, anonymous men. The fetish would present itself fully in The Angelic Conversation and best during a scene in The Last of England, where two terrorist-masked men would fuck on top of a British flag. More importantly, we first encounter the character of opposition in Jarman's films. After a discussion with Bradford, we came to realize that this character exists in most every of Jarman's films, the cunning provocateur, sort of like a Neanderthal Iago from Othello. This character is featured in both The Garden and Edward II as the instigator of humiliation or destruction of the central figure. He exists as Maximus (Neil Kennedy) in Sebastiane, a man of vulgar speech and carnal nature. In one particular scene (pictured above), he takes black chalk and rubs it across his lips and eyebrows like a sinister application of make-up designed not to be a beauty product, but the very opposite. Though Jarman is known for his more "traditionally" experimental works, Sebastiane is no less of a cinematic experiment. He replaces narrative with mood and feelings, and while this replacement may be the driving force behind some of Antonioni's best work, it's altogether different here. Above all, Sebastiane is a gorgeous mood poem set in a fantasy land that's half homoerotic wet dream (I hate that term) and nightmare. There are two opposing worlds: the world of royal decadence and of isolated peasantry. Both diverge, but exist within the same film world. In this world, "faith," especially of the Christian leaning, doesn't exist as we know it. When Sebastiane tells Justin (Richard Warwick) of why he chooses to endure such torture for this God of his, he speaks of God's beauty, "more beautiful than Adonis," and we can't help but take that statement literally. God is quite the "other man" that Sebastiane will not betray for the lust of Severus. This sounds a bit porny, but this is the fantasy world that Jarman and Humpfress have artfully (not pornographically) created, a world where men speak in vulgar Latin, barely wear clothes, and where even something as pure as "faith" can be sexual.

Though Jarman is known for his more "traditionally" experimental works, Sebastiane is no less of a cinematic experiment. He replaces narrative with mood and feelings, and while this replacement may be the driving force behind some of Antonioni's best work, it's altogether different here. Above all, Sebastiane is a gorgeous mood poem set in a fantasy land that's half homoerotic wet dream (I hate that term) and nightmare. There are two opposing worlds: the world of royal decadence and of isolated peasantry. Both diverge, but exist within the same film world. In this world, "faith," especially of the Christian leaning, doesn't exist as we know it. When Sebastiane tells Justin (Richard Warwick) of why he chooses to endure such torture for this God of his, he speaks of God's beauty, "more beautiful than Adonis," and we can't help but take that statement literally. God is quite the "other man" that Sebastiane will not betray for the lust of Severus. This sounds a bit porny, but this is the fantasy world that Jarman and Humpfress have artfully (not pornographically) created, a world where men speak in vulgar Latin, barely wear clothes, and where even something as pure as "faith" can be sexual.

2 comments:

I was reading a few months ago that the famous painting of St Sebastian with the arrow in him at the cross is the first "queer" moment for many young men, including the Japanese author Mishima who claimed that after he saw the painting and was so moved by the masculinity in the killing of such a poor young man, he knew he was gay. So my thought is I wonder if Jarman had a similar experience.

I'm not really sure about that. I'm sure there are essays written about St. Sebastian as a homosexual icon...

Post a Comment