The Intruder (L'intrus) - dir. Claire Denis - 2004 - France

The Intruder (L'intrus) - dir. Claire Denis - 2004 - FranceI guess I will use this as the formal warning that I normally give away key plot points in the films I review. It's hard to say that I'm giving away key points for L'intrus, but some might complain. Which is why I'm finding it so difficult to post my review of Sam Fuller's The Naked Kiss. But, alas...

You know how some people really have a liking toward film noir? Or some people really get off on Japanese cinema? Or the Nouvelle Vague? Well, I'm one of those people that gets off on contemporary French cinema. And, no, not L'auberge espagnole. I can find the most deeply flawed of the non-genre (J'aimerais pas crever un dimache [Don't Let Me Die on a Sunday] or Romance) to be far more salvageable than the average viewer just as a film noir lover can appreciate Orson Welles' The Lady from Shanghai far more than I can. Double Indemnity, it sure isn't. Out of all the contemporary filmmakers that fall into this category (Bruno Dumont, Gaspar Noé, Catherine Breillat, Olivier Assayas, etc), Claire Denis may be the most difficult to swallow. Her films are still polarizing, but not for the same reasons. She's equally as uncompromising as the others, but still for different reasons. Certain other directors are abrasive and confrontational (in a good way, mind you), while Denis is not. If I were to dub the New New Wave of French cinema as "French Extremism," Denis would probably not qualify, outside of her cannibal tale Trouble Every Day. Yet, as mentioned, the uncompromising nature of her work demands to be included with shock-fests like Anatomie de l'enfer [Anatomy of Hell] or Irréversible or Twentynine Palms.

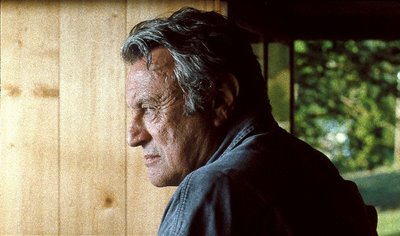

You know how some people really have a liking toward film noir? Or some people really get off on Japanese cinema? Or the Nouvelle Vague? Well, I'm one of those people that gets off on contemporary French cinema. And, no, not L'auberge espagnole. I can find the most deeply flawed of the non-genre (J'aimerais pas crever un dimache [Don't Let Me Die on a Sunday] or Romance) to be far more salvageable than the average viewer just as a film noir lover can appreciate Orson Welles' The Lady from Shanghai far more than I can. Double Indemnity, it sure isn't. Out of all the contemporary filmmakers that fall into this category (Bruno Dumont, Gaspar Noé, Catherine Breillat, Olivier Assayas, etc), Claire Denis may be the most difficult to swallow. Her films are still polarizing, but not for the same reasons. She's equally as uncompromising as the others, but still for different reasons. Certain other directors are abrasive and confrontational (in a good way, mind you), while Denis is not. If I were to dub the New New Wave of French cinema as "French Extremism," Denis would probably not qualify, outside of her cannibal tale Trouble Every Day. Yet, as mentioned, the uncompromising nature of her work demands to be included with shock-fests like Anatomie de l'enfer [Anatomy of Hell] or Irréversible or Twentynine Palms. The difficulty of L'intrus is not in the subject-matter as many of its contemporaries. Instead, it's difficulty is truly in Denis' narrative. Based on the novella of the same name by Jean-Luc Nancy, Denis explains in her interview on the Wellspring DVD about how the film was essentially her own mood piece on the story itself. What would be considered serious plot holes in a big-budget American film are essentially some of the strengths in Denis' film. Questions often go unanswered and, frustratingly, a lot of the story itself is left to be interpreted by the viewer. This is usually a good thing, as she establishes an intellectual trust with her viewer; however, a lot of L'intrus is utterly puzzling. We're told that Louis (Michel Subor) has a son (Grégoire Colin) whose life he is barely a part of. Yet, he goes out later searching for his son in Tahiti, where a local friend conducts a screening process to choose a son for him, as the mother will not allow Louis to see the boy/man. Call me a fucking moron if you will, but I have no idea what was going on here.

The difficulty of L'intrus is not in the subject-matter as many of its contemporaries. Instead, it's difficulty is truly in Denis' narrative. Based on the novella of the same name by Jean-Luc Nancy, Denis explains in her interview on the Wellspring DVD about how the film was essentially her own mood piece on the story itself. What would be considered serious plot holes in a big-budget American film are essentially some of the strengths in Denis' film. Questions often go unanswered and, frustratingly, a lot of the story itself is left to be interpreted by the viewer. This is usually a good thing, as she establishes an intellectual trust with her viewer; however, a lot of L'intrus is utterly puzzling. We're told that Louis (Michel Subor) has a son (Grégoire Colin) whose life he is barely a part of. Yet, he goes out later searching for his son in Tahiti, where a local friend conducts a screening process to choose a son for him, as the mother will not allow Louis to see the boy/man. Call me a fucking moron if you will, but I have no idea what was going on here. Though perhaps not as apparent as something like Vincent Gallo's The Brown Bunny, L'intrus is a very interior film. Most of what we see is inside of Louis' mind, and seldom does Denis clue us into this. Scenes pass by our eyes without Louis in sight. In fact, several scenes introduce us to completely foreign characters that appear (?) to have no connection to the film at all. Yet we have a crisp understanding of the roles of certain characters. Katia Golubeva, one of the many Denis regulars in the film (Subor also worked with Denis in Beau travail), plays a mysterious Russian woman, credited simply as Young Russian Woman, to whom Louis pays a large sum of money and who seems to be following him around the world. Some critics named her "The Angel of Death," which makes plenty of sense considering Louis pays her for the heart transplant to continue his life. And yet, she's still not finished with him. Other characters play less understood roles, like Béatrice Dalle as the "Queen of the Northern Hemisphere," as she's credited. She appears to have a purposeless role as a neighbor of Louis' who runs a dog shelter, yet it's her face we see before the end credits appear. Is she also a figment of Louis' imagination? This is far less clear in the film.

Though perhaps not as apparent as something like Vincent Gallo's The Brown Bunny, L'intrus is a very interior film. Most of what we see is inside of Louis' mind, and seldom does Denis clue us into this. Scenes pass by our eyes without Louis in sight. In fact, several scenes introduce us to completely foreign characters that appear (?) to have no connection to the film at all. Yet we have a crisp understanding of the roles of certain characters. Katia Golubeva, one of the many Denis regulars in the film (Subor also worked with Denis in Beau travail), plays a mysterious Russian woman, credited simply as Young Russian Woman, to whom Louis pays a large sum of money and who seems to be following him around the world. Some critics named her "The Angel of Death," which makes plenty of sense considering Louis pays her for the heart transplant to continue his life. And yet, she's still not finished with him. Other characters play less understood roles, like Béatrice Dalle as the "Queen of the Northern Hemisphere," as she's credited. She appears to have a purposeless role as a neighbor of Louis' who runs a dog shelter, yet it's her face we see before the end credits appear. Is she also a figment of Louis' imagination? This is far less clear in the film. Most of what I'm saying sounds like pretty severe criticism. Yet, I was completely glued to my TV screen. Denis' less successful films (Vendredi soir [Friday Night]) have the tendancy of giving the viewer too much (too much for Denis is an extremely less amount that... say Crash). Her most successful ones (at least the ones that make my toes curl) tend to have formed a severe distance from the viewer (Beau travail, Trouble Every Day). L'intrus is probably a notch below Beau travail or Trouble Every Day, if only because its evasiveness comes off a bit more frustrating than the other two. Denis gives us the makings of a potential weep-fest: a "heartless" (get it?) man searching for his son and a new heart. Yet she gives us nothing further, and this is to her benefit. While watching, her strength as a director can go unnoticed, but upon reflection, you realize that the initial thoughts that the film loses steam in its final half-hour makes complete sense. L'intrus is all about Louis and Subor as Louis (which Denis explains quite well in broken English on the DVD), so that the film appears far more confused and flimsy in the end is a totally conscious decision as (here comes your spoiler) Louis' body begins to reject the new heart. L'intrus is a quietly menacing film from its opening camera address from Golubeva to the haunting title-card, lit by only a cigarette, and the even-more-haunting music loop that continues throughout the film. It's quite rewarding, but maybe you have to be a total gutter-slut for New French New Wave, like me, to truly appreciate it.

Most of what I'm saying sounds like pretty severe criticism. Yet, I was completely glued to my TV screen. Denis' less successful films (Vendredi soir [Friday Night]) have the tendancy of giving the viewer too much (too much for Denis is an extremely less amount that... say Crash). Her most successful ones (at least the ones that make my toes curl) tend to have formed a severe distance from the viewer (Beau travail, Trouble Every Day). L'intrus is probably a notch below Beau travail or Trouble Every Day, if only because its evasiveness comes off a bit more frustrating than the other two. Denis gives us the makings of a potential weep-fest: a "heartless" (get it?) man searching for his son and a new heart. Yet she gives us nothing further, and this is to her benefit. While watching, her strength as a director can go unnoticed, but upon reflection, you realize that the initial thoughts that the film loses steam in its final half-hour makes complete sense. L'intrus is all about Louis and Subor as Louis (which Denis explains quite well in broken English on the DVD), so that the film appears far more confused and flimsy in the end is a totally conscious decision as (here comes your spoiler) Louis' body begins to reject the new heart. L'intrus is a quietly menacing film from its opening camera address from Golubeva to the haunting title-card, lit by only a cigarette, and the even-more-haunting music loop that continues throughout the film. It's quite rewarding, but maybe you have to be a total gutter-slut for New French New Wave, like me, to truly appreciate it.

1 comment:

I love Denis, and I love this film. It fits into a weird invented subgenre that I seem to love, the type of film where I'm mesmerized even when I have no idea what's going on -- a category that would also probably include Inland Empire.

That said, I think the film makes a lot more sense once you read the essay it's based on, by Jean-Luc Nancy. The essay deals with foreign-ness and the concept of difference, in terms of the individual's sense of identity, the ways advances in medical science have changed that identity, and as a metaphor for immigration. Denis grafts the loose narrative about Subor's character onto these concerns, but the film retains to some degree the essayistic character of its source. It's a fascinating essay on its own terms, too, well worth tracking down for a read.

Post a Comment