Shortbus

Shortbus - dir. John Cameron Mitchell - 2006 - USA

I recall a moment of my adolescence. As a middle schooler, I had a particularly strong fascination with the “actress” Alyssa Milano, forever known as Tony Danza’s tomboy daughter in

Who’s the Boss? and, later, one of a trio of sisters who happen to be witches on

Charmed. She emitted such uncommon beauty as she blossomed from girl to woman, yet still with a youthful innocence. I was enthralled to see she would be taking the Drew Barrymore role in the direct-to-video sequel to a film I once held in high regard,

Poison Ivy. I ran to my video store on a Tuesday to pick up

Poison Ivy II: Lily, only to then have this deep-seeded guilt take over me, as uncommon as I thought her beauty to be. The film played upon her image as the good girl, thrown into a world of aberrant sexuality and deviance. Essentially an exploitation film banking on the pseudo-popularity of the original,

Poison Ivy II: Lily left me feeling unclean, showing me that innocence was meant to be preyed upon and that sex was dirty. To some extent, I’ve never really shaken those feelings, though

Poison Ivy II and Alyssa Milano are not solely to blame. In so many ways, cinema (and other medias) has taught the youth (especially in the era of home video) how to think, and in terms of sexuality, we see that is a dirty, scornful act. Roger Ebert mentioned in his review for Philip Kaufman’s

Henry and June the ridiculousness of it’s NC-17 rating, making a comparison to David Lynch’s

Blue Velvet. Though the sex is more abundant in

Henry and June, it’s more explicit in

Blue Velvet;

Blue Velvet was allotted with an R-rating, he suspects, because in the film sex is bad, sex is dirty. In

Henry and June, sex is pleasure. So basically a film where adults enjoy having sex without the bad, naughty consequences is not the image we want to project to our youth.

In many ways, John Cameron Mitchell’s

Shortbus is a revelation. Surely, you’ve heard about the unsimulated sex scenes, and perhaps you know that this was one of the stipulations of the casting of the film. Naturally, Scarlett Johansson and Hayden Christensen did not send in their audition tapes (though Mitchell admits that Joseph Gordon-Levitt of

Mysterious Skin and

Shadowboxer (!) did audition). Instead of acquiring star power, Mitchell enlisted real people, mostly untrained in acting, ranging from writers to musicians to friends of his. What most critics fail to reveal about the film though is that, not only is the sex a real afterthought of the film, but that in

Shortbus, sex is not dirty. When compared to the works of the French (Catherine Breillat, Bruno Dumont, Patrice Chéreau), Mitchell’s take on showing sex without quick editing or strategically placed plotted plants greatly differs from the clinical, theoretical, or shocking nature of films like

Romance or

Intimacy. In

Shortbus, characters have sex, but their sex best reflects both their inner conflicts and exterior ones. In some ways, it’s just something they happen to do, like blowing their nose or going to the bathroom. Before I even saw the film, I had told myself that I would spend as little time possible writing about the sex in

Shortbus, but I feel it necessary to state the contrary to the onslaught of critics who have found nothing better to say about the film.

Shortbus

Shortbus shows its characters as humans, human beings brought up with the ambush of media, technology, Prozac, religion, and Republicans. Most of the characters here have reached the point in their life where something is supposed to make sense, where they’re supposed to understand themselves completely, and, surprise, none of them have. Like so many films before it,

Shortbus is a chronicle of a generation, a generation of unfulfilled expectation and confusion. The central character of the film isn’t a person or a city (though New York City plays as important of a role as it does in Woody Allen’s aptly titled

Manhattan); instead, the location of the

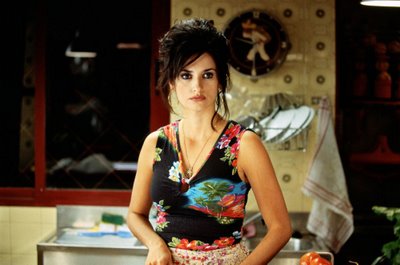

Shortbus club/commune serves as the point everything seems to come back toward. Sofia (Sook-Yin Lee) is a married relationship counselor who’s “pre-orgasmic.” James (Paul Dawson) and Jamie (PJ DeBoy) are in a long-term relationship that they want to open up with other people. Severin (Lindsay Beamish) is a dominatrix, afraid of what will happen to her if she ever has to leave New York. All of the characters are products of our times. Sofia and her husband Rob (Raphael Barker) practice new age methods in dealing with their marital problems. James, always with video camera in hand, and Jamie want to break free from the constraints of heterosexually-created monogamy and, at the same time, not become gay stereotypes. Ceth (Jay Brannan) uses his picture phone as a mirror and carries around a device that finds his closest mate. In certain films, the announcement of its time and place by either cultural or generational colloquialisms creates an irreversible time stamp that can be both distracting and significant of its fleetingness. In

Shortbus, these elements are essential. Like the 90s films of Gregg Araki, Mitchell exposes the immediate;

Shortbus takes place during a very specific time and place, which, in turn, becomes a broader statement of not just the characters, but the generation itself.

Yet, to call

Shortbus merely a chronicle of a generation would be to ignore its emotional depth and strength. Mitchell developed the screenplay and characters with his actors, and this is most apparent. Even the smallest of characters resonate with humanity and multiple facets. Perhaps because she’s given the most screen time, Sook-Yin Lee surfaces as the most remarkable of the unanimously excellent group. In nearly every scene, her Sofia shows us our answers in her face. Dialogue, though frequently poignant, doesn’t truly take us into Sofia as much as Sook-Yin Lee’s face does. There’s a large part of me that wants to reject things very fundamentally emotional or surface-level, but often I can’t bring myself to resist. Labeling

Shortbus as surface-level would be an incorrect statement, however, as the film successfully investigates the inner workings of so many varied characters. Perhaps it comes from a direct relationship to the struggles, pursuits, and desires of the characters, but Shortbus made me question, “when a film affects my emotions, is it necessarily a bad thing?” If I find myself sobbing to

The Other Sister, I’d say yes, but

Shortbus isn’t overtly manipulative and strikes against chords that aren’t normally affected by cinema.

Steven Spielberg made a statement that, in Bush’s second term, filmmakers have become more aggressive and piercing with their work. Sure, he was probably talking about his own

Munich and films like

Brokeback Mountain, but he’s not off the mark.

Shortbus is probably one of the more daring films to have come out of the United States since Bush was reelected, but not for the reasons everyone would make you assume.

Shortbus makes the bold statement that sex isn’t dirty, that we aren’t happy, but, refreshingly, that there are glimmers of hope within our own chaotic world. If there’s one thing to “learn” about

Shortbus, it’s that we need to find our community and that problems are not solved alone. The film certainly isn’t preachy about this point, but I've found myself wondering that it might not have been so bad if they did. If you leave the theatre with just a bunch of penises and vaginas in your head, just recognize that

Shortbus wasn’t made for you.

The OH in Ohio - dir. Billy Kent - 2006 - USA

The OH in Ohio - dir. Billy Kent - 2006 - USA