Somersault - dir. Cate Shortland - 2004 - Australia

Somersault - dir. Cate Shortland - 2004 - AustraliaThere are numerous ways that important facets of films can become oblivious to the audience member. In some cases, a reference or issue is lost in time - a moment that was once relevant slips past the modern-day viewer. Often, things are lost in cultural differences - a German viewer might completely overlook a Japanese custom presented in the film. Seldom do these instances hinder a greater appreciation of a film, for the film should have qualities that expand beyond a cultural idiosyncrasy that escaped a particular audience. I don’t doubt there are films that will mean nothing to anyone outside of the time it was made or its country of origin, but those films seem hardly worthy of mention (if I could even think of one). This can also be applied on a more personal level, naturally. When dealing with sentimentality, a filmmaker runs the risk of alienating a good chunk of its audience (really, this could also be said with a director who chooses not to communicate to their audience in this way). Sentimentality asks for an audience member to, at the very least, understand where this is coming from. On a higher level, it asks for you to relate the images and feelings onscreen with your own life. When done poorly, the film can easily turn into a disaster. Even when done well, there’s going to be plenty of people who won’t relate (and maybe they’re the people you don’t want to do so). To grasp Somersault, the first feature by Cate Shortland, one must take into account all of these things.

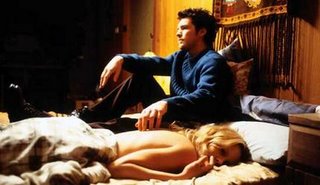

I read a review of Michael Haneke’s Caché in which a critic commented that the classism within the film went largely over the heads of the American audience. Naturally, there is plenty more for a viewer to take in, even if the dealings with class don’t particularly resonate. The same can be said for Somersault. As Americans, we do not understand class as people of other countries might, and this is truly key to following the course of action in the film. The central figure Heidi (Abbie Cornish) is routinely discriminated by others because of her lower class. The first night she meets Joe (Sam Worthington), he refuses to take her to his parents’ luxurious house and rents a motel; the next day, he lies and tells his father he stayed at a friends’ house. Initially, I was blind to his motives. He’s probably in his mid-twenties, which eliminated the possibility that he might be hiding an affair from his family, yet it all made sense when discrimination continued to fall upon Heidi from other characters. Class may be a strong, fluid theme throughout the film, but not so much to alienate us. As good films work, Somersault is not hindered by this cultural difference.

I read a review of Michael Haneke’s Caché in which a critic commented that the classism within the film went largely over the heads of the American audience. Naturally, there is plenty more for a viewer to take in, even if the dealings with class don’t particularly resonate. The same can be said for Somersault. As Americans, we do not understand class as people of other countries might, and this is truly key to following the course of action in the film. The central figure Heidi (Abbie Cornish) is routinely discriminated by others because of her lower class. The first night she meets Joe (Sam Worthington), he refuses to take her to his parents’ luxurious house and rents a motel; the next day, he lies and tells his father he stayed at a friends’ house. Initially, I was blind to his motives. He’s probably in his mid-twenties, which eliminated the possibility that he might be hiding an affair from his family, yet it all made sense when discrimination continued to fall upon Heidi from other characters. Class may be a strong, fluid theme throughout the film, but not so much to alienate us. As good films work, Somersault is not hindered by this cultural difference. A film critic is supposed to be impartial, yet I can surely say I’m not. I bring my own personal experience and my own prejudices to the seat. When I write about films then, I don’t try to hide this, though a certain distance is certainly essential if I want anyone to connect to what I’m saying, which is almost exactly the way Somersault unfolds. Shortland does not stray away from the sentimentality we would expect from the tale of a runaway teenage girl trying to pick up her life on her own; Somersault is a bit more maudlin than a film like My Summer of Love or Presque rien (both of which take place during similar moments in youth, which I wrote about here). I commended Olivier Assayas’ Clean for its unsentimental intimacy, yet I’m finding myself praising Somersault for opposite reasons. On a personal level, the film connected with me deeply, allowing me to empathize with characters and relate situations (and, more importantly, sensations, emotions, and feelings) to my own life. This can be applauded on its own for its accuracy and effectiveness in depicting subtle feelings that appear to be prevalent in the process of growing up. Its true strength though is Shortland’s ability to make a subtle and quiet film that doesn’t bore or nauseate. After Heidi and Joe’s first meeting, the film splits in two, insisting upon following Joe now, as well as Heidi, in his loneliness. This could have been a mistake, but, in considering the sentimentality, it keeps the film from being alienating and introspectively suffocating.

A film critic is supposed to be impartial, yet I can surely say I’m not. I bring my own personal experience and my own prejudices to the seat. When I write about films then, I don’t try to hide this, though a certain distance is certainly essential if I want anyone to connect to what I’m saying, which is almost exactly the way Somersault unfolds. Shortland does not stray away from the sentimentality we would expect from the tale of a runaway teenage girl trying to pick up her life on her own; Somersault is a bit more maudlin than a film like My Summer of Love or Presque rien (both of which take place during similar moments in youth, which I wrote about here). I commended Olivier Assayas’ Clean for its unsentimental intimacy, yet I’m finding myself praising Somersault for opposite reasons. On a personal level, the film connected with me deeply, allowing me to empathize with characters and relate situations (and, more importantly, sensations, emotions, and feelings) to my own life. This can be applauded on its own for its accuracy and effectiveness in depicting subtle feelings that appear to be prevalent in the process of growing up. Its true strength though is Shortland’s ability to make a subtle and quiet film that doesn’t bore or nauseate. After Heidi and Joe’s first meeting, the film splits in two, insisting upon following Joe now, as well as Heidi, in his loneliness. This could have been a mistake, but, in considering the sentimentality, it keeps the film from being alienating and introspectively suffocating. Without question, there are problems with Somersault alongside the wonderful moments. While a scene where Heidi notices a man staring at her from his car amiably impedes expectation, the functionality of other minor characters prove all-too-convenient. Somersault never overwhelms us with its dramatic affectations, though some of Shortland’s visuals a bit too radiant for the film. Cultural and personal distances aside, the film succeeds also because of Shortland’s approach to her two characters. They are steadily compelling souls (and well-played by the actors), and she presents their actions without being didactic or naïve. Their flaws make up their character and allow for natural interior and exterior conflict. Within its own unofficial genre (of which there are many others), Somersault falls somewhere in the top tier, benefiting highly from Shortland’s impressive mix of both sentimental and serene beauty.

Without question, there are problems with Somersault alongside the wonderful moments. While a scene where Heidi notices a man staring at her from his car amiably impedes expectation, the functionality of other minor characters prove all-too-convenient. Somersault never overwhelms us with its dramatic affectations, though some of Shortland’s visuals a bit too radiant for the film. Cultural and personal distances aside, the film succeeds also because of Shortland’s approach to her two characters. They are steadily compelling souls (and well-played by the actors), and she presents their actions without being didactic or naïve. Their flaws make up their character and allow for natural interior and exterior conflict. Within its own unofficial genre (of which there are many others), Somersault falls somewhere in the top tier, benefiting highly from Shortland’s impressive mix of both sentimental and serene beauty.

No comments:

Post a Comment